Project summary

The Carers’ Music Fund was a trailblazing two-year programme exploring how regular, social music-making for female carers could help improve their wellbeing.

The Department of Culture, Media and Sport awarded Spirit of 2012 £1.5m through the Tampon Tax Fund which was set up to allocate the money generated from the VAT on sanitary products to projects that improve the lives of disadvantaged women and girls. Spirit ringfenced a further £400,000 for access costs and alternative provision for participants’ loved ones.

Whilst campaign groups such as Carers UK and The Carers Trust have long highlighted the challenges unpaid carers experience in having time for themselves, we found limited examples of funded programmes that explicitly took a test and learn approach to removing barriers to their participation in arts and culture. Spirit of 2012 had previously funded high-quality projects supporting carers and their loved-ones to participate in activities together – this project was different for us in exploring both the value and the practicalities of funded projects just for the carers themselves.

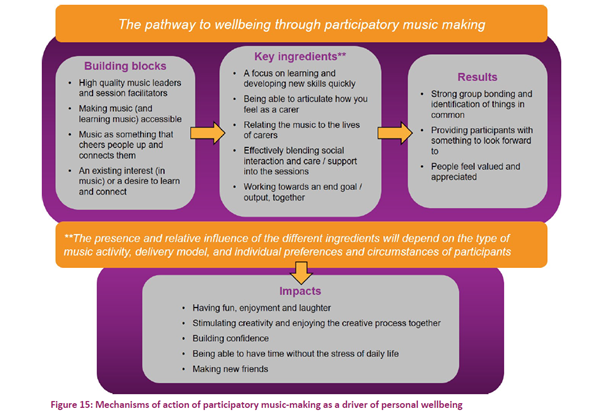

Alongside ten diverse grants, a mix of music and carers organisations, the project was underpinned by an innovative learning partnership made up of The What Works Centre for Wellbeing, Carers UK, The Behavioural Insights Team and Apteligen. This had the dual aim of explicitly supporting grantees to use insights from wellbeing research and feeding that research back into wider policy and practice.

The ten projects were:

- Sound Creators (UK Youth, £234,996): ran music sessions like DJ-ing and choir singing with young female carers in youth clubs in places such as Wigan, Birmingham, Bolton.

- Sound Out (Jack Drum Arts, £149,251): brought together female carers in County Durham, including recently resettled Syrian mother, for songwriting, community singing, and samba drumming to help them build confidence and connect with others.

- Women’s Work (Oh Yeah Music Centre, £59,800): Working in Belfast, this project offered music sessions for female carers in a variety of circumstances, including those looking after older family members with a dementia, recently settled Syrian families, and mothers with an interest in the music industry who had put their careers on hold to care for others.

- Tàlaidhean Ùra [New Lullabies] (Feis Rois, £59,998): brought mothers of new babies in rural Inverness together to share experiences and create their own lullabies, inspired by folk music from around the world.

- Monster Extraction (My Pockets, £156,651): worked with female carers in Hull and East Yorkshire to write music that gave voice to the struggles and “monsters” they face in their daily lives.

- Noise Solution (Beat Syndicate, £227,271.50): offered young carers in Suffolk one-to-one music mentoring and group music-making sessions, using digital tools.

- Project Alaw (Barnardo’s, £55,618): ran music workshops for girls and young women in caring roles in Merthyr Tydfil, helping them connect with others in similar situations.

- MyMusic (Northamptonshire Carers, £210,202): provided music-making opportunities for a wide mix of carers — older carers already in choirs, young carers aged 7–17, mother-daughter carers, and women caring for loved ones with dementia.

- Hidden Voices (Midlands Arts Centre, £219,999): offered music activities for women caring for people with autism, older female carers, and women from the Chinese Community Centre

- Bang The Drum (Blackpool Carers, £238,864): worked with the Grand Theatre in Blackpool to give female carers of all ages respite through creative expression and music-making.