UK Youth’s EmpowHER programme, match funded with the #iwill Fund, provides young women and girls with opportunities to make change in their communities.

Impact & Learning

Key achievements

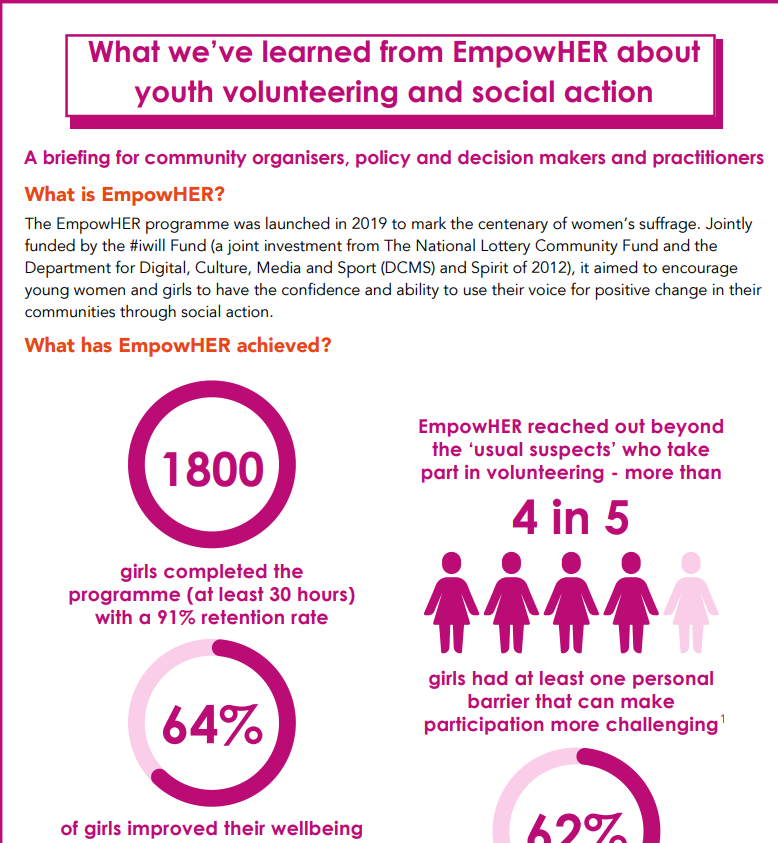

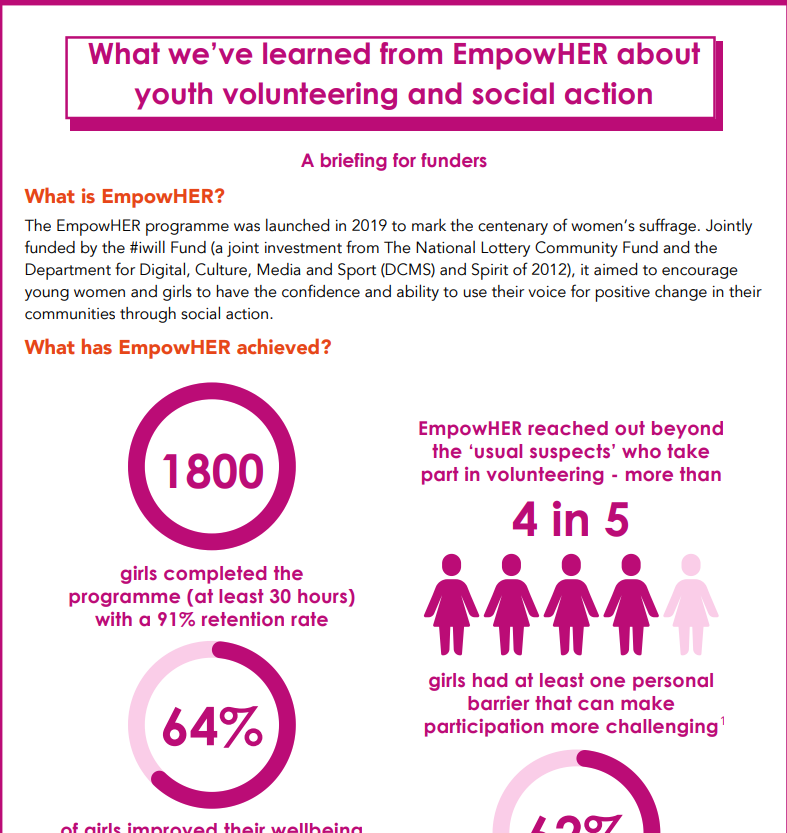

- 1,880 girls completed the initial programme – a 91% retention rate; a further 746 girls took part in EmpowHER legacy

- The original EmpowHER grant led to over 240 social action projects reaching over 20,000 people. The 79 social action projects set up as part of EmpowHER Legacy reached more than 30,000 people.

- Wellbeing cost effectiveness analysis conducted by PBE showed that the programme represented good value for money, with £5 in benefits for every £1 spent.

- Young women and girls completing EmpowHER experienced an average improvement of 0.95 life satisfaction points over a period of around 4.5 months. [For context, the average increase in wellbeing for an unemployed adult finding a job is around 0.5 life satisfaction points.]

- At the same time, matched sample analysis showed in the absence of the programme similar young women and girls typically experienced a decline in wellbeing of around 0.4 life satisfaction points. The project was having a protective impact in addition to the boost in wellbeing seen amongst participants. This means that the total wellbeing impact that can be attributed to EmpowHER is likely to be around 1.3 life satisfaction points.

- EmpowHER reached out beyond the ‘usual suspects’ who take part in volunteering – more than 4 in 5 girls had at least one personal barrier that can make participation more challenging

Key learning

Volunteering is an effective mechanism for improving young women’s wellbeing. This programme deliberately reached out to girls with low wellbeing. Many young people are struggling with low self-esteem and feeling pessimistic about the future. As described above, subjective wellbeing improved significantly across the programme – and the effect was more pronounced for girls with the lower starting points. Volunteering is neither a panacea for youth mental health issues, nor a substitute for medical and therapeutic support. However, our evidence suggests that well-structured, supportive social action programmes can play a powerful role in improving wellbeing. Researchers heard from one young women who said that her social action had “saved her life” by giving a sense of “purpose and responsibility, which was taken away when I was struggling and not coping”. Whilst this experience may be exceptional, the data strongly supports the fact that through volunteering young people developed a sense of agency, purpose and optimism about the future that improves overall wellbeing.

Develop an evaluation strategy that enables grant holders to apply lessons during the project, not just at its end: EmpowHER was broken down into four cohorts of activity, with funding provided for learning and reflection points of two months in between each cohort. This allowed the in-house evaluation team to share evidence with youth workers throughout the programme, rather than provide them with a summary at the end. This worked particularly successfully with EmpowHER, where the whole evaluation was done by an internal team. Even where organisations would prefer an external evaluation, there are clear benefits to funding internal staff capacity to review what the evaluation is telling them throughout the project and make changes to delivery as a result.

To maximise the gains from youth social action, funders and policymakers should look to incentivise partnership working. Young people and youth organisations worked in partnership with national organisations (British Red Cross and Young Women’s Trust), their schools, and many local organisations to create their projects, leading to unexpected collaborations which continued beyond the scope of the original programme. In the Leaders of the Future research, UK Youth found that 75% of youth organisations who took part in youth social action said they had strengthened existing community links, 75% said they had created new ones. Community organisations often lack the time and resource to collaborate, and beginning new partnerships can be risky if funders expect things to go right all the time. One of the secrets to EmpowHER’s success was the attention UK Youth and British Red Cross paid to building and maintaining relationship between local and national partners, at a local level, and between young people and those who were supporting them.

Plan for measuring community benefit from the start. Among the main reasons for funding social action to improve wellbeing above other activities is the ‘double benefit’ – the good it brings to the community, as well as to the volunteers. However, getting data on those specific benefits is difficult programmes where each group is working to a different goal. For example, how do you compare a campaign to change PE-kit to increase girls’ confidence, with volunteering at a COVID-19 vaccine centre, or a befriending scheme at a residential care home? At the outset, Spirit of 2012 agreed with UK Youth that it would be the responsibility of girls running each project to think about what success would look like and reflect on whether they had made a difference. However, as we did not want to give up the goal of understanding broader community benefits at the programme level, we decided to explore the effect of social action on cohesion. UK Youth measured whether girls were more likely to meet with people who are different to them and more likely to trust others, and in parallel, looked at how social action changed adults’ perceptions of young people in their community. Understanding community benefit is important and needs a proportionate but ambitious approach planned in from the start.

EmpowHER Legacy showed that a lower-cost model using the EmpowHER toolkit could still support girls into high quality social action in a way that youth organisations found rewarding. However, it did not provide us with the robust evidence base to understand what impact a reduced cost-per-head had on the wellbeing outcomes evidenced in EmpowHER. The decision not to collate ONS4 subjective wellbeing measures was made because the level of funding to each partner organisation was (by design) significantly less in the legacy programme than in the first phase of EmpowHER. The decision for proportionate evaluation understandable but also a missed opportunity. There is a strong case for further cost-effectiveness research exploring what level of central support is needed to achieve the wellbeing outcomes we saw in this programme.